This resource has been created as pre-reading for a session I have been invited to lead with students on the MSc Dietetics at UCL. It is my attempt at answering the question: ‘Is there any point in dieticians knowing about learning theory? (professionally I mean, given that it is, of course, inherently interesting!). However, I think it is potentially of interest to anyone teaching!

(Listen 9mins 12 seconds or read below)

Rationale

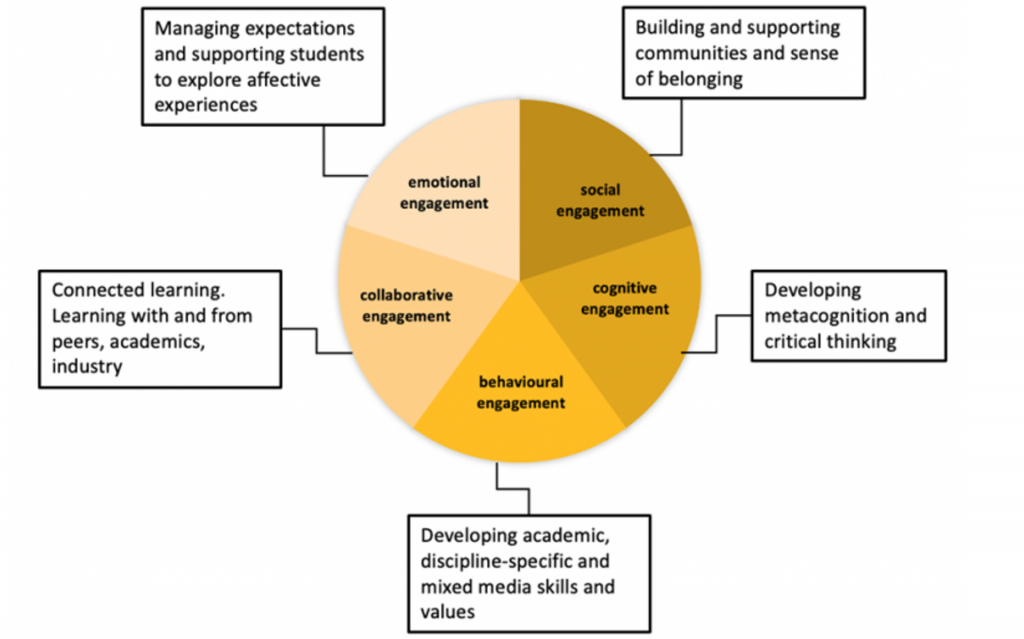

People with research or professional interests in educational psychology or teaching understandably and logically have an interest in learning theory. Whether theory provides a template for design of approaches to teaching, learning and assessment or offers an analytical lens to better understand what is happening at an individual or collective level, it makes sense that we challenge our assumptions, experiences and reflections through such theoretical lenses. But what of those whose relationship with teaching or with everyday human tendencies and behaviours is only a tangential part of their role? In any role where one person gives information to others, helps them to understand things or is responsible for changing (or helping to change) behaviours then understanding a little of how people learn will be beneficial. From my (lay) perspective, I imagine that common challenges in dietetics will be interpreting and conveying complex scientific information about nutrition and health and helping people to understand impacts and causation in relation to excess or absence in diet. Consideration of these challenges and issues that arise can be informed through theoretical lenses.

The learning theory landscape

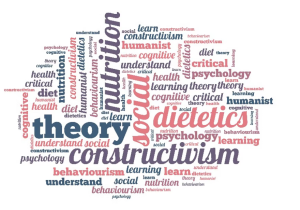

One of the problems with this is that a quick search for ‘theories of learning’ will present a dazzling, complex, sometimes-contradictory array of theories and ideas. It immediately raises several questions:

- Where do you start?

- How deep need you go?

- How can exposure to learning theory be applied in a meaningful way in context?

The answer to the first question may be ‘right here!’ if you have not studied learning theory before. The second question probably has the same answer as to the question: ‘How long is a piece of string?’ and will inevitably be determined by academic, research and professional roles and interests. The third question is one that we will try to get to grips with here and in the forthcoming session.

Like any other academic field, learning theory has its groupings and areas. The landscape isn’t always represented the same way: you will sometimes see theorists in one category, then another, which can be confusing. This may be due to classification differences, or because the theorist has developed their position over time. To complicate things further, the term ‘theory’ is used to cover a variety of models, approaches and techniques, and often defined by different people in different ways. That said, complication need not be a problem: rather than seeking firmly defined boundaries, think more in terms of spectra and Venn diagrams, where things overlap and interconnect. A main use of theory is to shed light on our experience and help us reflect on – and even change – our practice.

The following theories are both broad and narrow and some can be seen as subsets or informed by wider/ earlier theories. Whether broad or narrow, generalised or specific they have been selected because I think they may be of use to those in the field of dietetics. However, you have more expertise than I do here so it is important your critical eye is focussed and alert. Remember, it is unlikely that you will read a theory, decide ‘ah ha! That’s me from now on’. Rather, you may read, think, reflect, apply and draw on a range of complementary (or contradictory) ideas and approaches as you develop techniques in your future roles as well as using theoretical lenses to better understand what has worked and what has not.

Broad theoretical ‘schools’

Behaviourist theories of learning see the learner as passive; they can be trained using reward and punishment to ‘condition’ them to behave in particular ways (famous theorists in this domain include Pavlov and Skinner whose reach extends into popular understandings unlike most other domains of theory). Learning is seen as a change in behaviour. In health education the role of the expert might be to provide incentives or find ways to disincentivise certain behaviours. Consider the cost of tobacco products and the gruesome images on the packaging. What is the thinking behind this? Can the cost and images be credited with the continuing fall in numbers of smokers?

Cognitivist theories of learning see the learner as actively processing information rather than just being ‘conditioned’ by various stimuli. Cognitivists are concerned with how learners process and remember information, and often test recall as a measure of learning. In health education the expert’s role is to convey information in ways that optimises recall and completeness. Consider the 5 portions of fruit/ veg a day campaign: Whilst there were certainly ‘rewards’ built into the design of the programmes (i.e. health benefits of eating 5 a day) there was also an emphasis on providing and reinforcing information about nutrition and vitamins through attractive materials, booklets, leaflets, connections of school curricula and so on.

Constructivist theories of learning see the learner as an active participant in their own learning. The process of learning is not merely putting knowledge into an empty container. The ‘teacher’ presents knowledge, scenarios, resources, options and problems (or they gain it in another way) and in learning it students ‘construct’ the knowledge for themselves, linking it to what they already know. A variant of this is ‘social constructivism’, which holds that students’ construction of their knowledge is done with others. How might a dietician apply a constructivist approach when working with a client with type 2 diabetes who, by their own admission and despite worsening symptoms, persists in keeping a diet that is sugar, starch and salt rich?

Stop and think

Which broad theoretical approach can you see here?

At my local dentist surgery there is a display case with different sugary snacks, foods and drinks set out very neatly adjacent to piles of sugar equivalent to the actual amount in those foodstuffs. Each has a typed label (like in a museum) with the amount of sugar in grams. There are also a couple of low sugar items. There are no explicit warnings of the dangers of sugar to teeth.

Specific theories: How relevant / useful are these?

Situated Learning theory holds that relevance/ needs of learning are always embedded within a context and culture, so it’s best to teach particular materials within a relevant context – e.g. teaching clinical skills in a clinical setting. Within that context, students learn by becoming involved in a ‘community of practice’ – a group of practitioners – and through ‘Legitimate Peripheral Participation’ move from the periphery of this community towards its centre (i.e. the more expert and involved in practice they become, the closer they move toward the centre). (key names: Vygotsky, Lave)

Social Learning Theory views observation as key to learning; it holds that we learn through observing others, not just what they do but also the consequences of that. People learn from watching older or more expert people. An educator has a role in getting their attention, helping them remember and motivating them to demonstrate their learning. Behaviour is also affected by what they see being rewarded or punished. (key name: Bandura)

Mindset (motivational) Theory argues that if people believe that their ability to achieve something is fixed they have little chance of changing it and they therefore have a fixed mindset. To develop (i.e. learn), a growth mindset is needed and this is related to intrinsic self-belief. The educator’s role is to show belief, exemplify positive behaviours (e.g. hard work and effort should be valued not only results) and showing how to embrace ‘failure’ (key name: Dweck)

Critical Pedagogy is more of a movement than a theory: it holds that teaching cannot be separated from wider social and political concerns, and that educators should empower their ‘students’ to be active, critical citizens. Critical pedagogy is concerned with, whatever the subject, asking students to question hierarchies and power relations and to achieve a higher political consciousness. Paulo Freire, author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed (one of the first books of critical pedagogy) coined the ‘banking model’ in his critique of how some teaching aims to ‘fill’ students up with knowledge as though they are blank slates, merely receiving and storing knowledge. In addition, bell hooks’ work on intersectionality (complex layers of discrimination and privilege according to factors such as race, class, gender, sexuality and disability) might also lend a powerful lens to understand and challenge the nature and role of diet amongst groups as well as in individuals.

Session slides

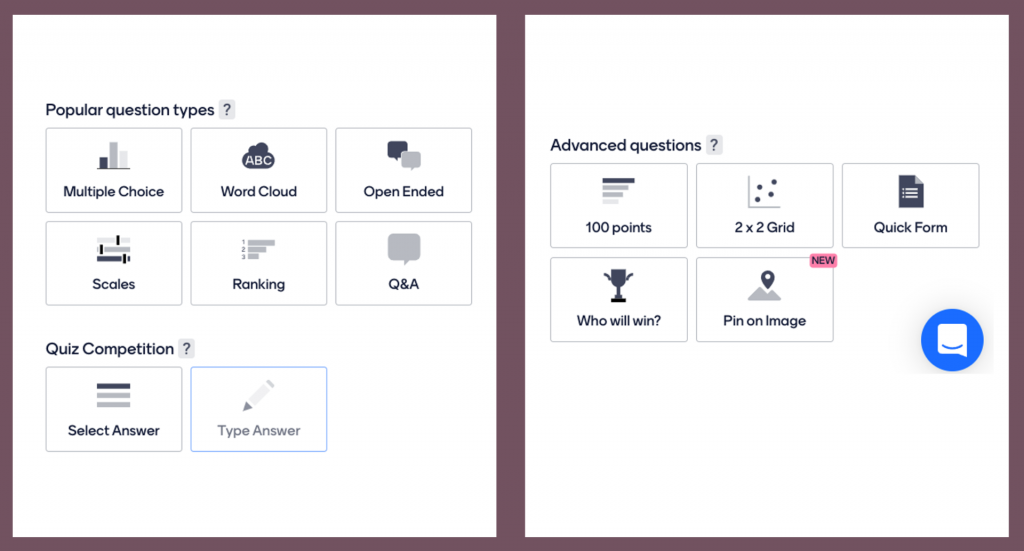

https://www.mentimeter.com/app/presentation/b198f152cb620471d75aaadbcc42c251/embed

Further reading

You may like to see things represented on a timeline with short, pithy summaries of key ideas. If so, try this site: https://www.mybrainisopen.net/learning-theories-timeline/

Donald Clark has written a huge amount about learning theory on his blog and this can be seen here if you prefer a dip in and search approach: https://donaldclarkplanb.blogspot.com/

A really accessible intro (as well as a much wider resource) is the encyclopaedia of informal learning: https://infed.org/learning-theory-models-product-and-process/

This resource was produced by Martin Compton. The Theoretical schools material was adapted from resources created by Emma Kennedy, Ros Beaumont & Martin Compton (UoG, 2018)