Audio version (Produced using speechify text to voice- requires free sign up to listen)

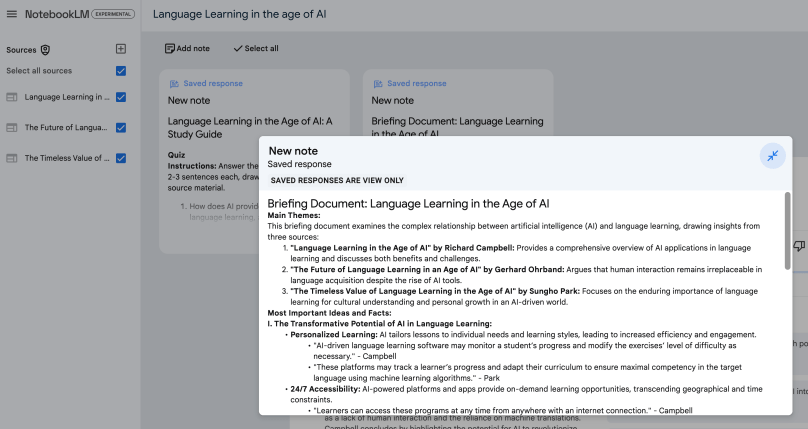

While we collectively and individually (cross college and in-faculties) reflect on the impacts over the last year or so of (Big) AI and Generative AI on what we teach, how we teach, how we assess and what students can, can’t should and shouldn’t be doing I am finding that (finally) some of the conversations are cohering around themes. Thankfully, it’s not all about academic integrity as fascinating as that is). Below is my effort at organising some of those themes and is a bit of a brain dump!

Balancing institutional consistency with disciplinary diversity

One of the primary challenges we face is how to balance the need for institutional consistency with the fact that GenAI is developing in diverse ways across different disciplines and industries. This issue is particularly pertinent at multi-disciplinary institutions like KCL, where we have nine faculties, each witnessing emerging differences not just between faculties but between departments, programmes, and even among colleagues within the same programme.

The fractious, new, contentious, ill-understood, unknown, and unpredictable nature of GenAI exacerbates this challenge. To address this, we are adopting a two-pronged approach:

1. Absolute clarity about the broad direction: ENGAGE at KCL (not embrace!) with clear central guidance that can be adapted locally, allowing a degree of agency.

2. A multi-faceted approach to evolving staff and student literacy, both centrally and locally, recognising that we all know roughly nothing about the implications and what will actually emerge in terms of teaching and assessment practices.

What we are not doing is articulating explicit policy (yet) given the unknowns and unpredictability but we are trying to make more explicit where existing policy applies and where there tensions or even perceptions of contradictions.

Enabling innovation while supporting the ‘engagement’ strategy

To enable and support staff in innovating with GenAI while fostering engagement and endeavouring to ensure compliance with ethical, broader policy and even legal requirements, our multi-faceted approach includes:

1. Student engagement in research, in developing guidance and in supporting literacy initiatives

2. Supported/funded research projects to help diversify fields of interest, to build communities of enthusiasts and to share outcomes within (and beyond) the College.

3. Collaboration within (e.g. with AI institute; involvement of libraries and collections, careers, academic skills) and across institutions (sharing within networks, participating at national and international events; building national and international communities of shared interest).

4. Investment in technologies and leadership to facilitate innovation and more rapid pace where such innovation and piloting and experimentation has typically taken much longer in the past.

5. Providing spaces for dialogue such as student events, the forthcoming AI Institute festival, research dissemination events, workshops and a college-wide working group.

As we navigate this new territory, consistent messaging and clear guidance are paramount. We need to learn from others’ successes and mistakes while avoiding breaching data privacy or other ethical and legal boundaries inadvertently- in a fast moving landscape the sharing of experience and intelligence is essential. One example (from another university!) is the potential pitfall of uploading students’ work into ChatGPT to determine if an LLM wrote it, only to discover that this constitutes a massive data breach, and the LLM couldn’t even provide that information.

Fostering digital literacy and critical thinking

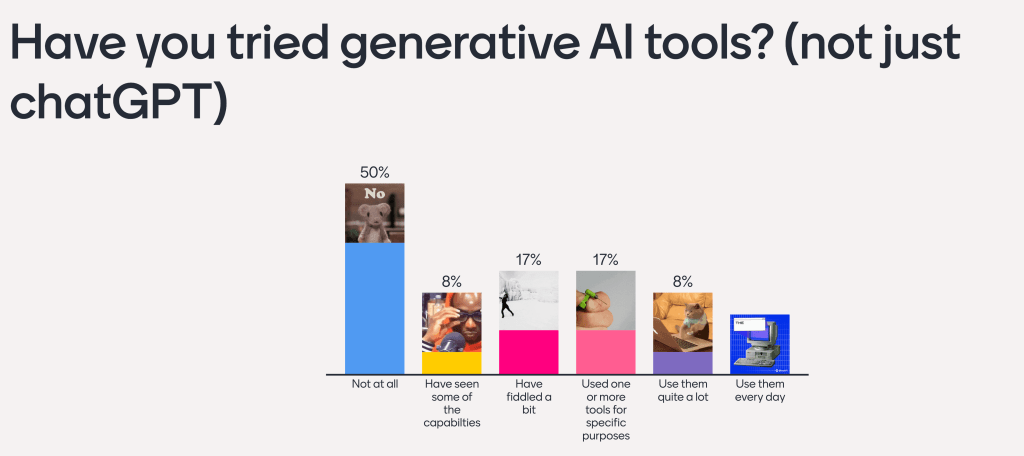

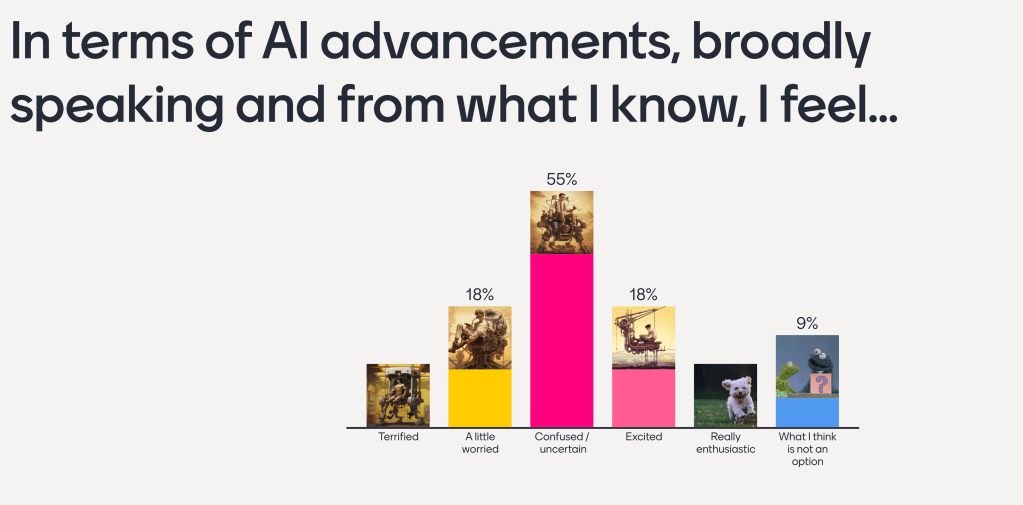

Everything above connotes learning (and therefore time) investment for all staff and students. Where will we find this time? Framed as critical AI literacy it is (imho) unavoidable even for the World’s leading sceptics. Wherever you situate yourself on the AI enthusiasm continuum (and I’m very much a vacillator and certainly not firmly at the evangelical end!), we have to address this and there’s no better way than first hand rather than (often hype tainted, simplistic) second-hand narratives peddled by those with vested interests (whether they be big -and small- tech companies with a whizzy tool or detector to sell you or educational conservatives keen to exploit a perceived opportunity to return to halcyon days of squeaky-shoed invigilation of exams for everyone for everything).

My biggest worry for the whole educational sector (especially where leadership from government is woolly at best) is that complexity and necessary nuancing of discussion and decision-making will signal a threatening or punitive approach to assessment or an over-exuberant, ill-conceived deal with the devil…both of which of will be counterproductive if good education is your goal. In my view we should:

1. Work with, not against, both students and the technology.

2. Model good practices ourselves.

3. Accept that mistakes will be made, but provide clear guidelines on what is and is not advised/permitted for any given teaching or assessment or activity.

4. Drive the narratives more ourselves from within the broader academy- stop reacting; start demanding (much easier collectively, of course).

At KCL, we have implemented three “golden rules” for students to mitigate risks during the transition to better understanding:

Golden Rule 1: Learn with your interactions with AI, but never copy-paste text generated from a prompt directly into summative assignments.

Golden Rule 2: Ask if you are uncertain about what is allowed in any given assessment.

Golden Rule 3: Ensure you take time before submission to acknowledge the use of generative AI.

Empowering critical and creative engagement

This is easy to set as a goal but of course much harder to realise. To empower all students (and staff) to engage critically and creatively with GenAI tools, we must acknowledge the potential benefits while addressing justified concerns. In an environment of reduced real-terms funding, international student recruitment challenges, and widespread redundancies in several HE instituions, some colleagues might view GenAI as yet another burden. I have been encouraging colleagues (with one eye on a firmly held view that first-hand experience equips you much better to make informed judgements) to look for ways to exploit these tech in relatively risk-free ways not only to build self-efficacy but also to shift the more entrenched and narrow narratives of GenAI as an essay generator and existential threat! Some examples:

1. Can you find ways to actually realise workflow optimisation?: GenAI tools offer amazing potentials for translation, transcript generation, meeting summaries, clarifying and reformatting content.

2. Accessibility and neurodiversity support: Many colleagues and students are already benefiting from GenAI’s ability to present content in alternative formats, making it easier to process text or generate alt-text.

3. Educational support in underserved areas: GenAI tools at a macro level could potentially support regions where there are too few teachers but also on a micro level can enable students with complex commitments to access a degree of support outside ‘office hours’

Implications for curriculum design, teaching and assessment

The advent of GenAI has potential implications for curriculum design, instructional strategies, and assessment methods. One concern is the potential homogenisation (and Americanisation) of content by LLMs. While LLMs can provide decent structures, learning outcomes, and assessment suggestions, there is a risk of losing the spark, humanity, visceral connection and novelty that human educators bring.

However, this does not have to be an either/or scenario and I think this is the critical point to raise. We can leverage GenAI to achieve both creativity and consistency. For example, freely available LLMs can generate scenarios, case studies, multiple-choice questions based on specific texts, single-best-answer databases, and interactive simulations for developing skills like clinical engagement or client interaction. A colleague has found GenAI helpful in designing Team-Based Learning (TBL) activities, although the quality of outputs depends on the tool used and the quality of the prompts, underscoring the importance of GenAI literacy.

When discussing academic integrity and rigour, we must separate our concerns about GenAI from broader issues around plagiarism and well-masked cheating, which have long been challenges. We need to re-evaluate why we use specific assessments, what they measure overtly and tacitly, and the importance of writing in different programmes.

Moving beyond ‘Cheating’ and ‘AI-Proofing’

To move the conversation around AI and assessment beyond ‘cheating’ and ‘AI-proofing,’ we must recognise that ‘AI proofing’ is an arms race we cannot win. We also need to accept that we have lived for a very long time with very varied definitions of what constitutes cheating, what constitutes plagiarism and even the extent to which things like proof-reading support are or should be allowed. I thin k the time now is for us to re-evaluate everything we do (easy!) – our assessments, their purposes, what they measure, the importance of writing in each programme, and what we define as cheating, plagiarism, and authorship in the context of GenAI. If we do this well, we will surface the tacit criteria many students are judged on, the hidden curricula buttressing programme and assessment design and covert (even often from those assessing) privileges that dictate the what and how of assessments and the ways in which they are evaluated.

Ethical dilemmas: Energy consumption and a whole lot more

Many have written on the many controversies GenAI raises- copyright, privacy, exploitation, sustainability. One is energy consumption. While figures vary, some suggest that using an LLM for a basic search query costs 40 times more in cooling. Shocking! Conversely, others argue that using LLMs to generate content that would otherwise be time-consuming and laborious could be less costly in terms of consumption. What to think?! At the very least and as technology improves, we must distinguish between legitimate, purposeful use and novelty or wasteful use, just as we should with any technology. But we need to find trusted sources and points of referral as, in my experience at least, a lot of what I read is based on figures that are hard to pin down in terms of provenance and veracity.

We cannot pretend that that the copyright, data privacy, lack of transparency, and the exploitation of human reinforcement workers issues do not exist- and these are challenges compounded by the tech industry’s race for a sustainable market share. But we should be wary of ignoring pre-existing controversies, being inconsistent in the ways we scrutinise different tech and, from my point of view at least, fail to recognise the potentials as a consequence of some of the more shocking and outlandish stories we hear. Again, we come back to complexity and nuance. Currently, education seems to be in reaction mode, but we need to drive the narratives around these ethical concerns.

Intellectual property rights, authorship, and attribution

As I say above, we need to re-examine the fundamentals of higher education, such as our definitions of authorship, writing, cheating, and plagiarism. For example, while most institutional policies prohibit proofreading, many students from privileged backgrounds have long benefited from having family members review their work – a form of cultural capital and privilege that is generally accepted and not questioned even if, by letter of the academic integrity law, such support is as much cheating as getting a third party piece of tech to ‘proof read’ for you.

The opportunity for students from diverse backgrounds, including those who find conventional reading and studying challenging, to leverage GenAI for similar benefits is a reality we must address. Unless the quality of writing or the writing process itself is being assessed, we may need to be more open to how technology changes the way we approach writing, just as Google and word processing revolutionised information-finding and writing processes. I think we (as a sector) have realised that citation of LLMs is inappropriate but for how long and in which disciplines will we feel the need to make lengthy acknowledgements of how we have used these tech?

Regardless of the discipline, engaging with GenAI is crucial – not doing so would be irresponsible and unfair to our students and ourselves. However, engagement also connotes investment in time and other resources, which raises the question of where we find those resources.