I did a session earlier today for the RAISE special interest group on AI. I thought I’d have a bit of fun with it 1. because I was originally invited by Dr. Tadhg Blommerde (and Dr. Amarpreet Kaur) who likes a heterodox approach (see his YouTube channel here) and 2. Because I was preparing on Friday evening and my daughter was looking over my shoulder and suggesting more and more memes. Anyway, I was just reading the chat back and note my former colleague Steve asked: “Is the rest of the sector really short of memes these days now that Martin has them all?” I felt guilty so decided to share them back.

My point: There’s a danger we assume students will invariably cheat if given the chance. This meme challenges educators to reconsider what they define as cheating and encourages transparent, explicit dialogue around academic integrity. What will we lose if we assume all students are all about pulling a fast one?

My daughter (aged 13) suggested this one. How teachers view ChatGPT output: homogenised, overly polished essays lacking individuality. My daughter used the ‘who will be the next contestant on ‘The Bachelor’ (some reality show I am told) image to illustrate how teachers confidently claim they can spot AI-generated assignments because “they all look the same.” My point: I think this highlights early scepticism about AI-produced writing but that we should as educators consider the extent to which these tools have evolved beyond initial assumptions and remind our students (and ourselves) that imperfections and quirks can define a style. Just ask anyone reading one of my metaphor-stretched, overly complex sentences. Perhaps, for too long we have over-valued grammatical accuracy and formulaic writing?

My point: It’s not just about AI detectors of course. It’s more that this is an arms race we can’t win. If we see big tech as our enemy then fighting back with more of their big tech makes no sense. If we see students as the enemy then we have a much bigger problem. Collective punishment and starting with an assumption of guilt are hugely problematic in schools/ unis much as they are in life and tyrannical societies in general. When it comes to revisiting academic integrity I am keen discuss what it is we are protecting. I am also very much drawn to Ellis and Murdoch’s ‘responsive regulation’ approach. I don’t think I’m quite on the same page regarding automated detection but I do agree regarding the application (and resourcing of) deserved sanction for the ‘criminal’ (willful cheats) along with efforts to widen self-regulation and move as many students as possible from carelessness (or chancer behaviours) to self-regulation is critical.

Pretty obvious I guess but my point is this: We also need to resist assumptions that all students prioritise grades over genuine learning and creativity. Yes, there are those who are wilfully trying to find the easiest path to the piece of paper that confirms a grade or a degree or whatever. Yes, there are those whose heads may be turned by the promise of a corner-cutting opportunity. But there are SO many more who want to learn, who are anxious because they know others who are being accused of using these tech inappropriately (because, for example, they use ‘big’ words… really, this has happened). ALSO, we need to challenge the structural features that define education in terms of employability and value. I know how to use chatgpt but I am writing this. Why am I bothering writing? Because I like it. Because – I hope- my writing, even when convoluted (much like this sentence) is more compelling. Because it’s more gratifying than the thing I’m supposed to be doing. Above all, for me, it’s because it actually helps me articulate my thoughts better. We must continue valuing intrinsic motivation and the joy students derive from learning and creating independently. But more than that: we need to face up to the systemic issues that drive more students towards corner cutting or willful cheating. By the way, I often use generated text in things I write. All the alt text in these images is AI generated (then approved / edited by me) for example.

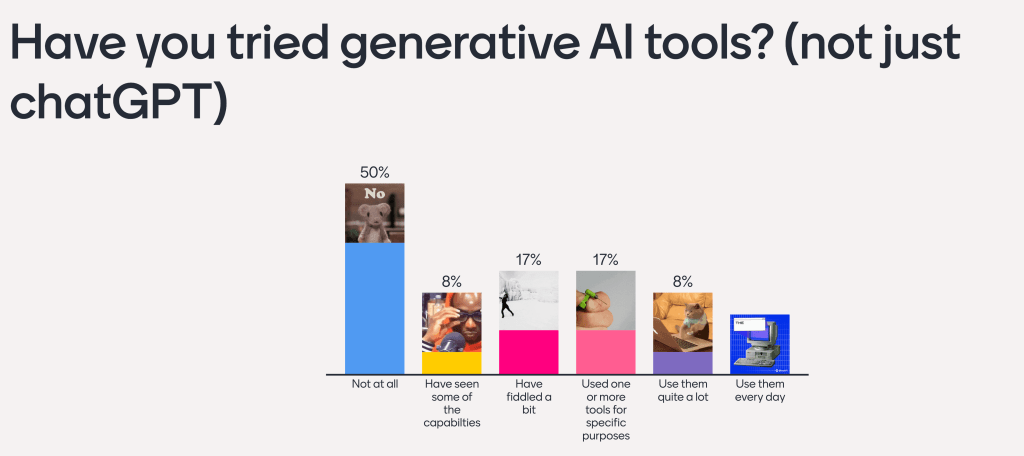

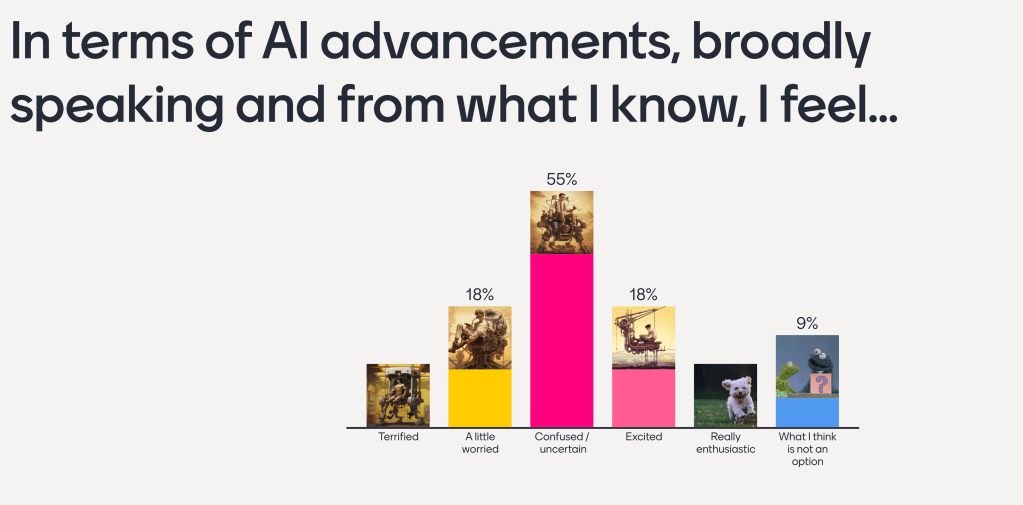

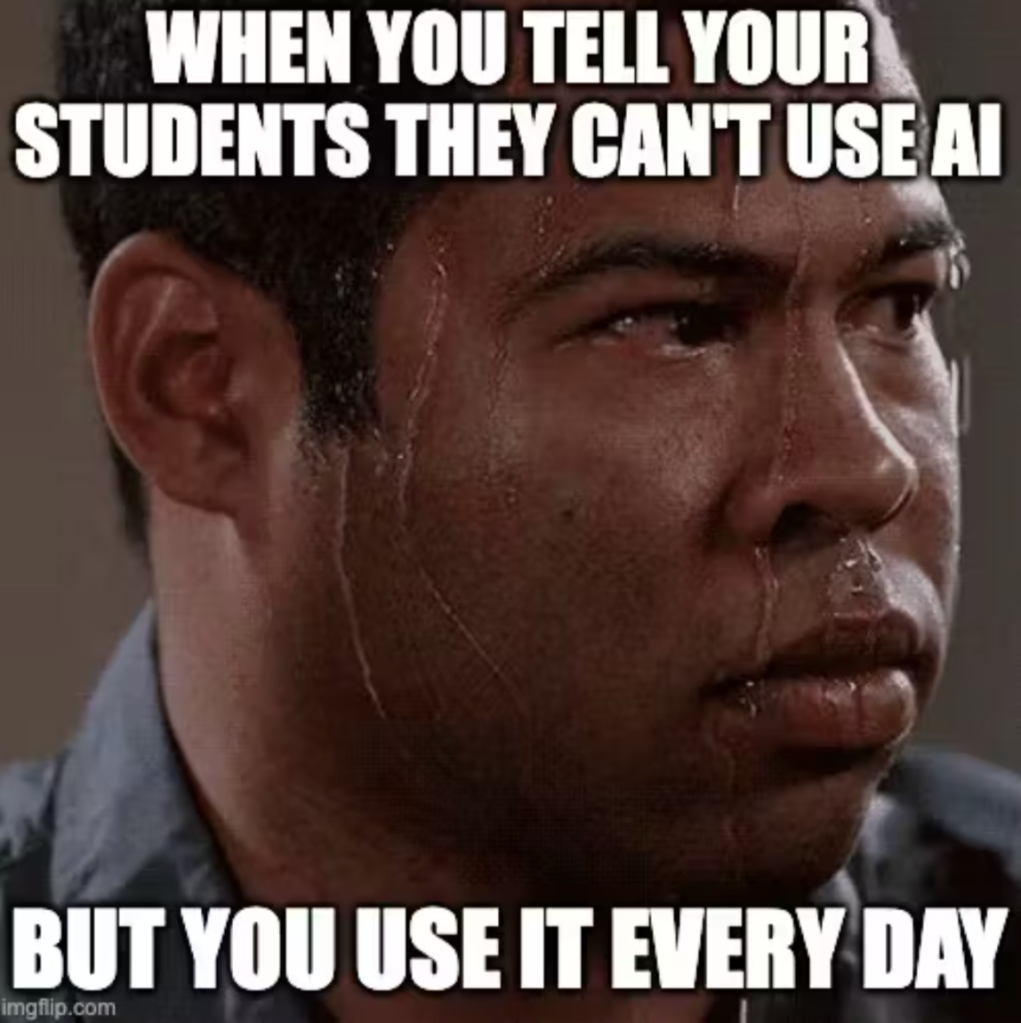

This leads me to the next one. I mean I do use AI every day for translation, transcription, information management, easing access to information, reformatting, providing alternative media, writing alt text… Many don’t I know. Many refuse; I know this too. But we are way into majority territory here I think. Students are recognising this real (or imagined) hypocrisy. The only really valid response to this I have heard goes something like: ‘I can use it because I am educated to x level. first year undergrads do not have the critical awareness or developed voice to make an informed choice’. I mean, I think that may be the case to an extent or in some cases but it reminds me a bit of the ‘pen licences’ my daughter’s primary school issued: you get one when you prove you can use a pencil first (little Timmy, bless him, is still on crayons). Have you seen the data on student routine use of generative AI? It elevates the tool to some sort of next level implement but is it even? I think I could make a better case for normalisation and acceptance of a future where human / AI hybrid writing is just how it is done (as per Dr Sarah Eaton’s work- note the firve other elements in the tenets.)

My point: The narratives around essential changes we need to implement ‘because of AI’ presents a false dichotomy between reverting to traditional exam halls or relying solely on AI detection tools. Neither option adequately addresses modern academic integrity challenges. Exams can be as problematic and inequitable as AI detection. It is not a binary choice. There are other things that can be done. I’ll leave this one hanging a bit as it overlaps with the next one.

My point: We need to critically re-evaluate how and why essays are used in assessment. We can maintain the essay but evolve its form to better reflect authentic, inclusive and meaningful assessments rather than relying on traditional, formulaic, high-stakes versions. Anyway I (with Dr Claire Gordon) have said it before, we already have a manifesto and Dr Alicia Syskja takes the argument to the next level here.

Really, though, you should have been there; we had a great time.