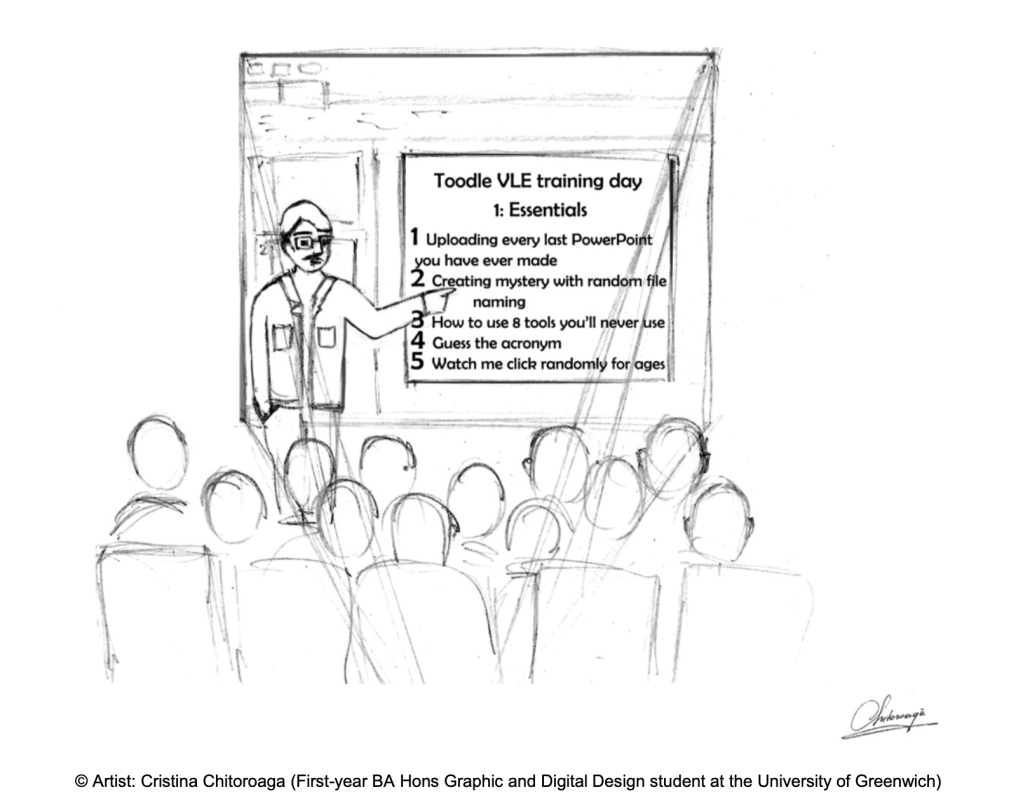

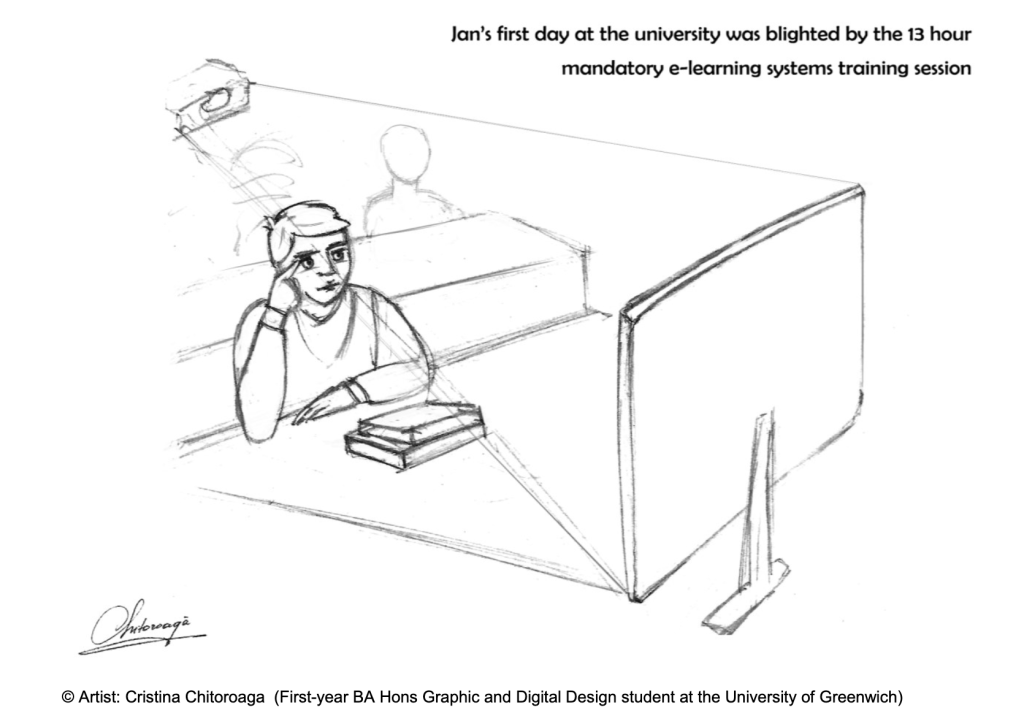

In 2018, Timos Almpanis and I co-wrote an article exploring issues with Continuous Professional Development (CPD) in relation to Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL). The article, which we published while working together at Greenwich (in Compass: Journal of Learning and Teaching), highlighted a persistent challenge: despite substantial investment in TEL, enthusiasm for it and use among educators remained inconsistent at best. While students increasingly expect technology to enhance their learning, and there is/ was evidence to supports its potential to improve engagement and outcomes, the traditional transmissive CPD models supporting how teaching academics were introduced to TEL and supported in it could undermine its own purpose. Focusing on technology and systems as well as using poor (and non modelling) pedagogy often gave/ give a sense of compliance over pedagogic improvement.

Because we are both a bit contrary and subversive we commissioned an undergraduate student (Christina Chitoroaga) to illustrate our arguments with some cartoons which I am duplicating here (I think I am allowed to do that?):

We argued that TEL focussed CPD should prioritise personalised and pedagogy-focused approaches over one-size-fits-all training sessions. Effective CPD that acknowledges need, relfects evidence-informed pedagogic apparoaches and empowers educators by offering choice, flexibility and relevance, will also enable them to explore and apply tools that suit their specific teaching contexts and pedagogical needs. By shifting the focus away from the technology itself and towards its purpose in enhancing learning, we can foster greater engagement and creativity among academic staff. This was exactly the approach I tried to apply when rolling out Mentimenter (a student response system to support increasing engagement in and out of class).

I was reminded of this article recently (because fo the ‘click here; clck there’ cartoon) when a colleague expressed frustration about a common issue they observed: lecturers teaching ‘regular’ students (I always struggle with this framing as most of my ‘students’ are my colleagues- we need a name for that! I will do a poll – got totally distracted by that but it’s done now) how to use software using a “follow me as I click here and there” method. Given that the “follow me as I click” is still a thing, perhaps it is time to adopt a more assertive and directive approach. Instead of simply providing opportunities to explore better practices, we may need to be clearer in saying: “Do not do this.” I mean I do not want to be the pedagogy police but while there is no absolute right way there are some wrong ways, right? Also we might want to think about what this means in terms of the AI elephant in every bloomin’ classroom.

The deluge of AI tools and emerging uses of these tech (willingly and unwillingly & appropriately and inappropriately) means the need for effective upskilling is even more urgent. However we support skill development and thinking time we need of course to realise it requires moving beyond the “click here, click there” model. In my view (and I am aware this is contested) educators and students need to experiment with AI tools in real-world contexts, gaining experience in how AI is impacting curricula, academic use and, potentially, pedagogic practices. The many valid and pressing reasons why teachers might resist or reject engaging with AI tools: workload, ethical implications, data privacy, copyright, eye-watering environmental impacts or even concern about being replaced by technology are a significant barriers to adoption. But adoption is not my goal; critical engagement is. The conflation of the two in the minds of my colleagues is I think a powerful impediment before I even get a chance to bore them to death with a ‘click here; click there’. In fact, there’s no getting away from the necessity of empathy and a supportive approach, one that acknowledges these fears while providing space for dialogue and both critical AND creative applications of responsibly used AI tools. In fact, Alison Gilmour and I wrote about this too! It’s like all my work actually coheres!

Whatever the approach, CPD cannot be a one-size-fits-all solution, nor can it rely on prescriptive ‘click here, click there’ methods. It must be compassionate and dialogic, enabling experimentation across a spectrum of enthusiasm—from evangelical to steadfast resistance. While I have prioritised ‘come and play’, ‘let’s discuss’, or ‘did you know you can…’ events, I recognise the need for more structured opportunities to clarify these underpinning values before events begin. If I can find a way to manage such a shift it will help align the CPD with meaningful, exploratory engagement that puts pedagogy and dialogue at the heart of our ongoing efforts to grow critical AI literacy in a productive, positive way that offers something to everyone wherever they sit of the parallel spectrums of AI skills and beliefs.

Post script: some time ago I wrote on the WONKHE blog about growing AI literacy and this coincided wiht the launch of the GEN AI in HE MOOC. We’re working on an expanded version- broadening the scope of AI beyond the utterly divisive ‘generative’ as well as widening the scope to other sectors of education. Release due in May. It’ll be free to access.