Hang on it was summer a minute a go

I looked at my blog just now and saw my last post was in July. How did the summer go so fast? There’s a wind howling outside, I am wearing a jumper and both actual long dark wintry nights and the long dark metaphorical ones of our political climate seem to loom. To warm myself up a little I have been looking through some tools that offer AI integrations into learning management systems (LMS aka VLEs)* rather than doing ‘actual’ work. That exploration reminded me of the first ever article I had published back in 2004. The piece has long since disappeared from wherever I save the printed version and is no longer online (not everything digital lasts forever, thank goodness) but I dug the text out of an old online storage account and reading it through has made me realise how much things have changed broadly while, in other ways, it is still the same show rumbling along in the background, like Coronation Street (but no-one really remembers when it went from black and white to colour).

What I wrote back then

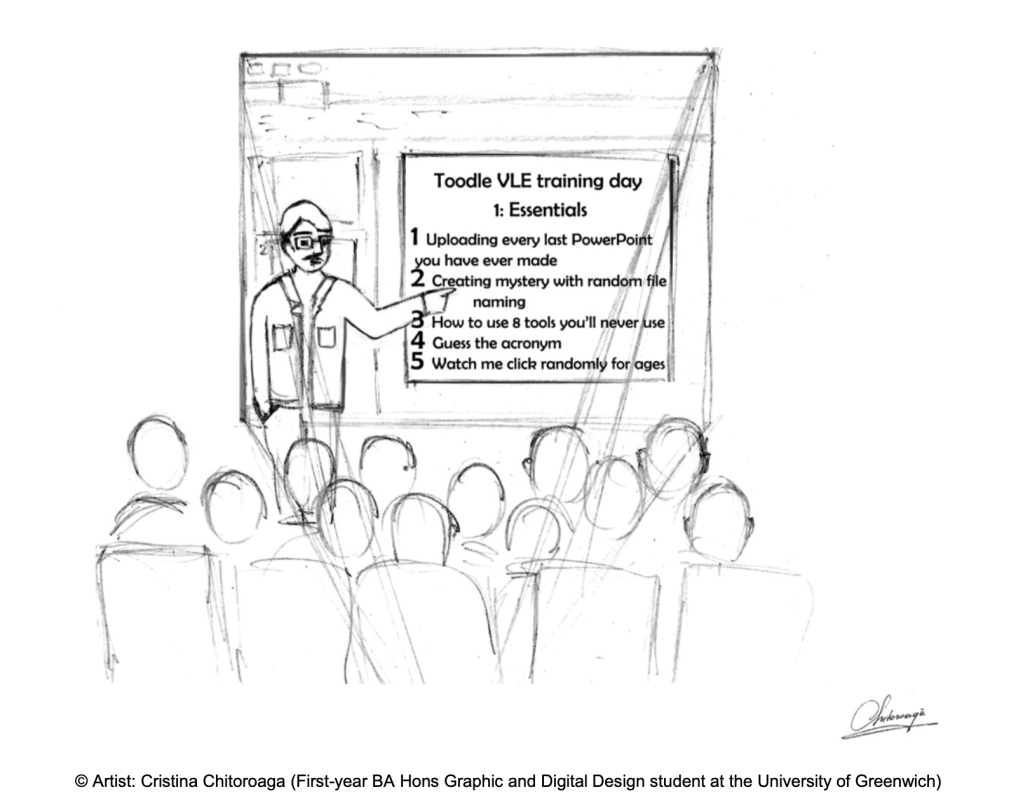

In that 2004 article I described the excitement of experimenting with synchronous and asynchronous digital discussion tools in WebCT (for those not ancient like me, Web Course Tools – WebCT- was an early VLE developed by the University of British Columbia which was eventually subsumed into Blackboard). I was teaching GCSE English and was programme leader for an ‘Access to Primary Teaching’ course and many of my students were part time so only on campus for 6 hours per week across two evenings. I’d earlier taught myself HTML so I could build a website for my history students- it had lots of text! It had hyperlinks! It had a scolling marquee! Images would have been nice but I knew my limits. When I saw WebCT, I was fired up by the possibilities of discussion forums and live chat. When I set it up and trialled it I saw peer support, increased engagement with tough topics, participation from ‘quiet’ students amongst other benefits. I was so persuaded by the added value potential I even ran workshops with colleagues to share that excitement.

See this great into to WebCT from someone in CS dept at British Columbia from 1998:

That is still me of course. My job has changed and so has the context, but the impulse to share enthusiasm for digital tools that foster dialogue and interaction remains why I do what I do. It was nice to read that and I felt a fleeting affection for that much younger teacher, blissfully unaware of the challenges ahead! Even so and forming a rattling cognitive dissonace that is still there, I was frustrated by the clunky design and awkward user interface that made persuading colleagues to use it really challenging. Log in issues took up a lot of time and balancing ‘learning’ use with what I then called ‘horseplay’ (what was I, 75?!) took a while to calibrate. Nevertheless, I thought these worth working through but, even with some evidence of uptake across the college I was at was apparent, there was a wider scepticism and reluctance. Why wouldn’t they? ‘it’s too complex’; ‘I am too busy’; ‘the way I do it now works just fine, thank you’. Pretty much every digital innovation has been accompanied by similar responses; even the good ones! I speculated about whether we needed a blank sheet of paper to rethink what an LMS could be, but concluded that institutions were more likely to tinker and add features than to start again.

2004? Feels like yesterday; feels like centuries ago

It was only 2003–4 (he says, painfully aware that I have colleagues who were born then), yet experimenting with an LMS felt novel and that comes over really clearly in my article. If you’d asked me this morning when I started using an LMS I might have said 1998 or 99. 2003 feels so recent in the contexct of my whole teaching career. What the heck was I doing before all that? Thinking back I realise that in my first full time job there was only one computer in our office and John S. got to use that as he was a trained typist (so he said). And older than me. In the article I was carefully explaining what chat and forums were and how they were different from one another, so the need for that dates the phenomeon too I suppose. Later, after moving to a Moodle institution, I became e-learning lead and engaged with JISC working groups- a JISC colleague who oversaw the VLE working group jokingly called me Mr Anti-Moodle because I was vocal in my critiques. It wasn’t quite acccurate- I was critical for sure but then, as now, I liked the concept but disliked the way it worked. Persuading people to adopt an LMS was hard as I said, and, while I have seen some brilliant use of Moodle and the like, my impression is that the majority (argue with me on this though) of LMS course are functional repositiories with interactive and creative applications the exception rather than the norm. The scroll of death was a thing in 2005 and it is as much of a thing now. It also made me think of current ‘Marmitey’ positions folk are taking re: AI. Basically, AI (big and ill defined as it usually is) has to come with nuance and understanding so binary, entrenched, one size fits all positons are unhelpful and, in my view, hard to rationalise and sustain.

The familiar LMS problem

Back to the LMS, from WebCT to Moodle and other common current systems, the underlying functionality has barely shifted (I mean from the perspective of your average teacher/lecturer or student). Many still say Moodle feels very 1990s (probably they mean early 2000s but I suspect they, like me, find it hard to reconcile the idea of any year starting with a 2000 could be a long time ago). Ultimately I think none of these systems offered a genuinely encouraging combination of interface and user experience and that is an issues that persists to this day. The legacy of those early design decisions lingers, and we are still working around them. People have been predicting the death of the VLE for years (including me) but it has not happened. When I first saw Microsoft Teams just before Covid, I thought here’s the nail in the coffin. I was wrong again. Maybe being wrong about the end of the LMS is another running theme.

Will AI change the LMS story?

So what about AI powered integrations? Will they revolutionise how the LMS works? Will they be part of the reason for a shift away from them? Unlikely in either sense is my best guess. Everything I see now is about embellishments and shortcuts that feed into the existing structure. My old dream of a blank-sheet LMS revolution has faded. Thirty years of teaching and more than twenty years using LMSs suggest that this is one component of digital education that will not fade away. The tools will keep evolving, but the slow, steady thrum of the LMS endures in the background. I realise that I have finally predicted non change so don’t bet on that as I have been wrong quite a bit in the past. What I do know is that digital discussions using tools to support dialogic pedagogies have persisted as have the issues related to them. Only 10-20% of my students use the forums! I hear that still. But what I realised in 2004 and maintain to this day is that 10-20% is a significat embellishment for some and alternative for others so I stick with what I said back then in that sense at least. Oh, and lurking is a legit and fine thing for yet others!

One of the most wonderful things about the AI in Education course (so close to 15,000 participants!) is the forums. They add layers of interest that cannot be planned or produced. I estimate only 10-15% of participants post but what a contribution they are making and its an enhancement that keeps me there and, I am convinced, adds real value to those not posting too.

*I’ll stick with LMS as this seems to be pretty ubiquitous these days though I am aware of the distinctions and when I wrote the piece about ‘WebCT’ the term VLE was very much go to.